The next right thing - Elsa, Anna, Olaf and two way door decision making

Technical decision making put to song

But how long will it take?

I had an interesting discussion with a startup CEO last month. I’d done a deep dive into their architecture and was discussing refactoring to address a root cause bottlenecking their progress. But what he wanted to focus on was timing, schedule and timing. It can be a valuable question - but not at this stage in this situation.

I’d been (as I’m want to do) asking a lot of questions to understand from their informed perspective what outcomes would bring true long term value. Eventually I heard “it seems you have a lot of questions, but I’d like to hear a strong view from you?” So with a deep caveat I shared my take on what I thought their core bottleneck was … and maybe how to fix it in a really direct way.

It seemed pretty clear their current systems state was problematic. Who wants their customers to be able to shoot themselves in the foot via a config file? But I wasn’t yet 100% convinced this was their only giant landmine. For example, they’d suggested that it was hard to close new sales with their aging UI. I was naturally skeptical - usually when people say their UI is ugly the business friction is more that the existing tool didn’t solve a big enough problem for customers to make it worth their while1. But I guess we weren’t going to have that part of the discussion….

Rather than debate the bottleneck and technical fix I suggested, the discussion took a hard turn into “how long would that take?”

This was not a super comfortable path for me. This CEO was very focused on nailing down an estimate, ahead even of discussing the benefits/downsides of the path. Sure, an estimate can be a reasonable shorthand that helps compare and contrast other ideas. For example - I know this discussion was naturally being compared to an internal go-forward plan.

I was sympathetic to wanting a clear, definitive answer. But as they say; for every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple and wrong2. This was one of those situations.

I think when you’re uncomfortable about something it pays to pause and try to determine if you’re uncomfortable because you’re scared (of being wrong) or because you think the question itself is wrong. No experienced manager is going to feel super awesome about being pushed hard for a specific timeline. Life experience teaches you that tight estimates usually don’t survive contact with reality and/or if you feel “safe” someone probably padded the hell out of the thing.3

In this case though I realized my discomfort came directly from the question clashing with my view of reasonableness/reality. Why would make anyone should believe an estimate for an extensive refactor I made after 8 hours alone with the codebase?

When pressed to answer an unanswerable question, sometimes it’s better to answer a different one.

I stammered out something both polite and unconvincing about the fallacy of anchoring on any estimate I provided at this point. Well into this embarrassment I remembered I have a principle here that might bridge both side’s needs. I proactively answered an alternate (and possibly better) question - “What would I suggest we do next given this hypothesis on prioritizing refactoring the trust bottleneck?”

Next I think I blurted out “I just don’t have enough information to give you an estimate of time or cost that you should believe, so here’s what I’d do next.”

Explaining that we could;

invest a day or two going deep on the hypothesis with key members of their tech team, and if it held up,

spend a time boxed period (say a week) doing a deeper estimate including what would need to be true to achieve the fastest possible path, and

Commit to another fixed period researching the actual DB structures to have a more data driven view how risky a migration would be. Researching and prototyping the hardest parts first.

Inside 2-4 weeks I think we’d have a much better view of the landscape as well as significant de-risking of the overall schedule. Being able to stop at any point if we had conviction their original plan was way better.

Put more simply - we’d identify the next most important knowledge needed to make a good planning decision and solve for that. Repeatedly making a series of better informed decisions until we had deeper confidence and a true plan. Thinking back on the conversation I’m sad to realize I think they took this as me unhelpfully hedging (not confident enough). Which was unfortunate because (a) I suspect this is causing them to underestimate the value of a pretty clever path that was proposed, (b) because I was hella confident that this method of planning beat pretend schedule certainty, and (c) it made me realize I wish I’d come up with the phrase that seemed to apply here “you can lead a horse to water but you can’t make them drink.”

Another key negative about the situation - their lack of enthusiasm kept me from sharing my pet name for this approach of de-risking execution. The “Frozen 2” approach. Yes - I’m about to make an off brand movie connection here. Not that I’m short of movie connections to technical themes. It’s just that they’re usually not Disney related4.

Frozen 2?

Frozen 2 came out in November of 2019, when my daughter was on the verge of turning 6, and at a time of year where outdoor adventures in the PNW were less fun than a few months earlier. This perfect storm5 of events contributed to Frozen 2 being pretty big hit with her - and me being open to seeing it whenever she asked. By my count she and I saw it theatrically 5 times. If it weren’t for Covid swooping in a few months later the number of viewings could have been a lot higher.

For sure, I enjoyed the film. I’m a sucker for talking snowmen and mega bonkers plot lines. Even so, around the 4th viewing my mind started to rebel drift. With these free cycles my brain sought deeper insights in the material. Deep as in the root cause of Galactic Empire’s troubles being an unsafe workspace for learning or something of that stature. Not just a quiet laugh on something funny slipped into the mix in the songs6.

What came out of that? A realization that the song “The Next Right Thing” was a catchy one line summary of a truth embedded in many strong decision processes. I guess I’ve been saving it for a substack post ever since7.

Turns out this approach has a more serious name

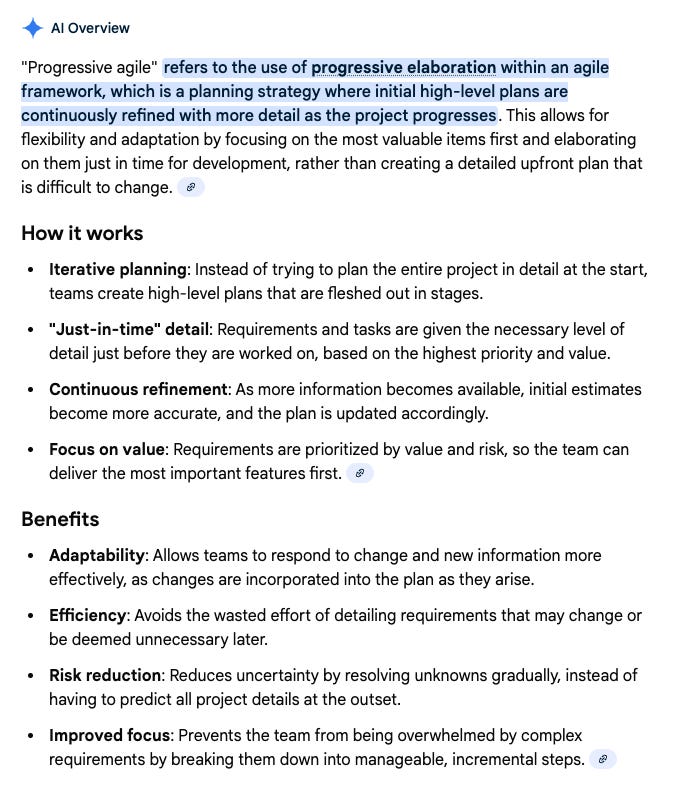

I’ve realized that what I was trying to suggest in that CEO meeting is often referred to as “progressive elaboration.” Occasionally being blended into the Agile universe into sometimes being referred to as “progressive agile.” According to Gemini it “refers to the use of progressive elaboration within an agile framework, which is a planning strategy where initial high-level plans are continuously refined with more detail as the project progresses.”

While perhaps apropos of nothing this progressive agile thing was interesting, and new to me, so I figured I’d just slip it in here.

Estimates likely won’t make you super accurate, but they will drive velocity

Some readers may remember my discussion of estimation as included in the best practices for multi-discipline pods article shared earlier this year. Much debate around estimates involves the cost of getting good estimates. Specifically, whether it’s worth the trouble in Agile processes and/or coupled with some talk about how dates aren’t important.

This is one of those topics that has merit in the nuance but can quickly be seen/branded as “this group of engineers isn’t serious about going fast or hitting dates.” I don’t especially feel like wading into that minefield at the moment. In my mind estimates are important because expressing your view as to how long something might take services several parallel purposes.

Estimates make clear the assumptions of the dev team, and the team member doing the estimation. If one person thinks a task will take days and another takes weeks - it’s important to notice that. Once there’s some convergence on roughly how long something will that, that enables rechecking if it’s worth engaging in the activity at all. Finally, it anchors any subsequent discussion about whether there are better approaches.

Before you send any hate mail

I’m not at all saying that a project cannot have hard dates. If you’re trying to launch something that’s only used once per year (say tax filing), or trying to coordinate all of Amazon to launch a new marketplace in a new country then not having a stake in the ground will cause endless chaos. But that’s because in those examples the date is the true priority, or is an input to alignment that’s hard to otherwise achieve. Bringing an abstract “dates don’t matter” mindset to a discussion as an engineering team with stakeholders is like bringing Schrödinger’s cat a knife to a gunfight. It’s unlikely to work out for you, and at best you’re gonna feel pretty silly once you realize what’s go.

Look… probably understand the point you’re trying to make with the whole “we don’t do target dates.” Agile is about delivering shippable results, incrementally. Flow and throughput are most important to get to that as quickly as possible. And lots of other sorts of justifying statements. But … and it’s a big “but” … this never lands the way you think it does. Generally it’s greeting with a level of enthusiasm usually reserved for the caterer who serves the bacon wrapped pork ribs at rabbi convention buffet8.

All that usually happens is whatever PM or other person you’re talking to immediately slacks me (or your equivalent) and asks “WTAF is up with the team that doesn’t care at all about hitting dates?” Then after I explain all of the background to them they just spend more time than is strictly healthy stuck in the mental model that anyone who says what you said must be really slow and phoning it in9. ;-)

Much better to be curious why the date is important in the other party’s world and work back from that.

What was the next right thing? In case you’re curious

In this case I believe my short term instincts were correct. The next best things to do were to (1) check if my hypothesis passed an initial sniff test (2) invest a day or two (more likely 3-8 hours) to have staff technologists poke at what would have to be true for it to be a solid approach, and (3) run a focused sprint to expose and assess technical risks (for example by scanning the actuals of the database situation - more no that in a sec). Basically what I suggested to them above - though it’s probably a smidge clearer now that I had the time to write about it. Clear writing being clear thinking and all that.

In case you’re really curious about this story at a slightly more detailed level. Based on what I’d heard from discussions and extrapolated from the codebase; their execution was going to be deeply challenged until they addressed an architecture issue enabling customers to make breaking changes by editing local files10. My thought was to break the bottleneck by allowing customers to edit their local config, but to disallow that being translated into alter_table commands (which turned their series of multi tenant DB’s into a random mish mash of stuff). Instead intercepting that workflow to translate “custom columns” into a more dynamic persistence such as structured JSON.

I was no more confident in my hypothesis than I would have been in a schedule to execute it (OK - I was more confident in the former than the latter). So it’s critically import to attempt to invalidate my assumptions by checking (a) someone doesn’t have disconfirming info on the tech team and (b) they’re not willing to staff up significantly just to cover this toil and free up time for other things. Though since customer trust is probably broken when the system stops working occasionally I still suspect (b) won’t be convincing on it’s own.

A small caveat

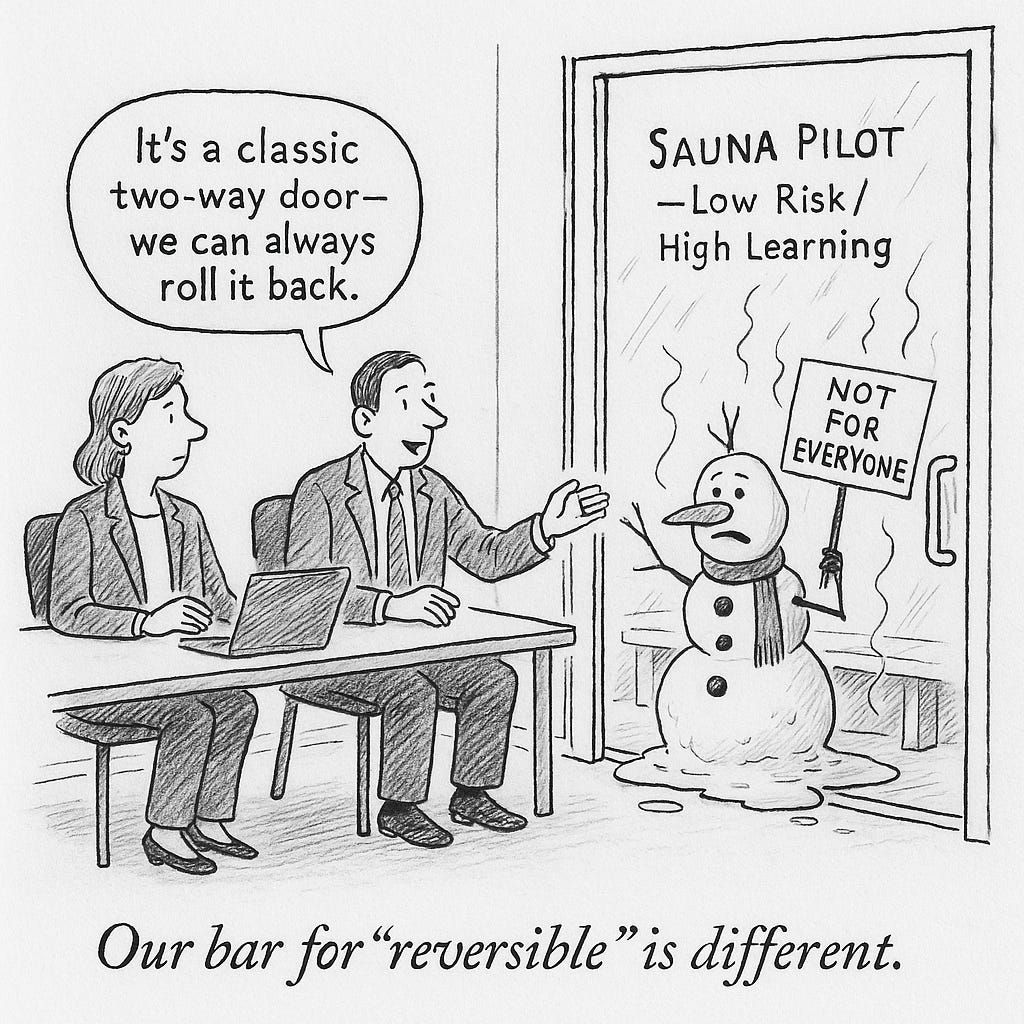

There’s a theory of decision making that basically points to the need to make decisions in a quick manner. “Don’t worry about making a wrong decision, because if that happens just make another decision.”

Generally I think this is right approach because even when you make good decisions (ie; given the information at the time you made the right one from an expected value perspective) things can still go badly. Even something you’re 85% sure of goes sideways 15% of the time - the quality of the decision isn’t the same as the result. However, this assumes the issue at hand is in the “two way door category.” Once you walk through that door it’s pretty easy to just go back to the other side.

The challenge however is that aome problems are very much in the “one way door” segment. These are decisions that once made are hard, impossible, or expensive to reverse. You may still resolve ambiguity in a stepwise way as you approach their event horizon by doing the best/right thing. But you should over-invest in decision quality as having to walk backwards will be a lot harder than walking forwards was.

If you look at easy Amazon seller tools (or a lot of things on Amazon) it wasn’t going to win ANY design awards. The pain points for sellers were real, and widely known. Sellers would complain, but it wasn’t enough to stop them from signing up in droves given the level of buyers they got access to once they were in the marketplace. This was true until it wasn’t - sellers in China were a lot less forgiving of crappy tools since the customer base was much smaller there. FWIW - a lot of super smart people worked very hard and the seller tooling got better. My point is that this was done after there was product market fit - the lack of great tooling couldn’t get in the way of such an incredible opportunity for sellers. Their struggle was worth it to them. If the value is high enough people can get past a lack of beauty. Also - see most of the Amazon shopping experience …

I’ve gotten in a new habit of researching the author of snappy quotes as I use them - to avoid a sharp observation from a super problematic individual. This one liner is generally credited to HL Menchken - who I don’t know much about but a quick survey seems to put him into the category of “not a mensch.” Bummer - but still a solid quote. Like many people I thought the quote I had in mind was Einstein’s - which I think would have been better. Seems a common misattribution due to Einstein’s comment that “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.” FWIW that’s also a fine reflection on the universe. That now concludes or brief foray into quote research.

An irony is that padding the hell out of a schedule often doesn’t really ensure you’ll finish on time anyway. Student Syndrome, and Parkinson’s Law will likely eat the buffer you think you had for lunch - plus you’ll likely burn a fair amount of trust once skeptical others start poking at individual parts of your plan. For a longer (but not that much longer) take on this and other project management practices read Goldratt’s Rules of Flow. It’s very helpful and more approachable than the original Theory of Constraints take on the topic of project management - Critical Chain.

Crap - It just hit me that Disney now owns Star Wars - so maybe they’re ALL Disney related. I would make some crack about that, but at least they’re not the ones who pretended Han didn’t shoot first. So I really cannot complain.

Sorry Francisco - I know you hate this expression. If you happen to know Francisco be sure to ask him why. It’s a “perfect storm” of reasoning combining historical meteorological knowledge, cognitive bias impacting decision making, and a irrational hatred of George Clooney. Well - one of those things may be me misremembering. Someday perhaps we can convince him to writeup his thoughts. I mean Francisco of course - but if someone knows Clooney that would work too.

On the laugh out loud moments of the Frozen franchise it’s hard to beat the line from Fixer Upper from the first film. “So he’s a bit of a fixer-upper, so he’s got a few flaws... his thing with the reindeer, that’s a little outside of nature’s laws!”.

Sorry - sometimes a lot of writing really is just an excuse to quote a Disney tune. If you were paying for this Substack I’d be more sympathetic to the complaint. ;-)

Actually - this is an iffy example because I suspect there would be a lot of interest in the pork product. There just wouldn’t be positive feelings that such a delicious looking thing was there taunting them.

Look, I’m sure there are exceptions to this rule in both directions. But I’ve seen this enough times to just say - “OK, but I think my point is worthwhile.”

This was an intentional editing of files (configs) to setup the product. It just seemed that because the edits triggered database table alters lots of bad things could happen if the changes were uncontrolled. Which they were.