The short meeting paradox

Why you should make your meetings longer, much longer. And some questions to use to make them better.

"People say nothing is impossible, but I do nothing every day" - Winnie the Pooh

“Delay is preferable to error - Thomas Jefferson

The short meeting paradox

How often have you had a problem at work that went on for months? When you look back, have you ever felt the core issue could have been sorted in 2-3 hours with the right people locked in a room? There was a time when I thought that my answer would be “heck no!!!” to this line of questioning. But that was before I was introduced to the innovation of the 30 minute meeting.

Almost everyone loves to hate meetings. Even one of the best books on how to use meetings more productively, Death by Meeting leans into the hating to hook the airport bookstore shopper with the catchy title. Businesses have fallen in love with the 30 minute meeting (or it’s cousin the 25 minute meeting because Google thinks we can trick ourselves into being on time somehow).

This won’t be a very long post by my standards, and for many it will seem obvious. But once you’ve seen the pattern it’s hard to unsee it. In this case that’s a good thing.

These short meetings can easily become a point in themselves. Extremely bad multitasking lurking in the guise of efficiency. A more productive course of action can often be triggered by asking “maybe you all should consider a mini-offsite or something?” If you don’t want to read the rest of this post - just try that for any thing you’ve met twice or more on without having the core problem being resolved. It’s an effective tripwire.

I’d already started writing this post in the background when I realized this pattern is just about “meetings.” It’s really about the dangers of reducing focus on something that would benefit disproportionally from being sorted out sooner vs. later. I was talking with a CEO who’d shared this great summary of the Palantir embedded engineering model with me. When we got to talking about it I realized he was describing in a different way the same core problem I’d been thinking about. In this case it’s physical separation of engineering from customers causing a challenge in converging to the highest value solution to build. But the solution is the same. Focus on how to get to value/resolution faster. Avoiding value destroying compromise but staying together long enough to really understand the problem and people. Even (especially) if the short term cost of that time investment may seem high. Otherwise you’re being pennywise but pound foolish.1

What to do instead

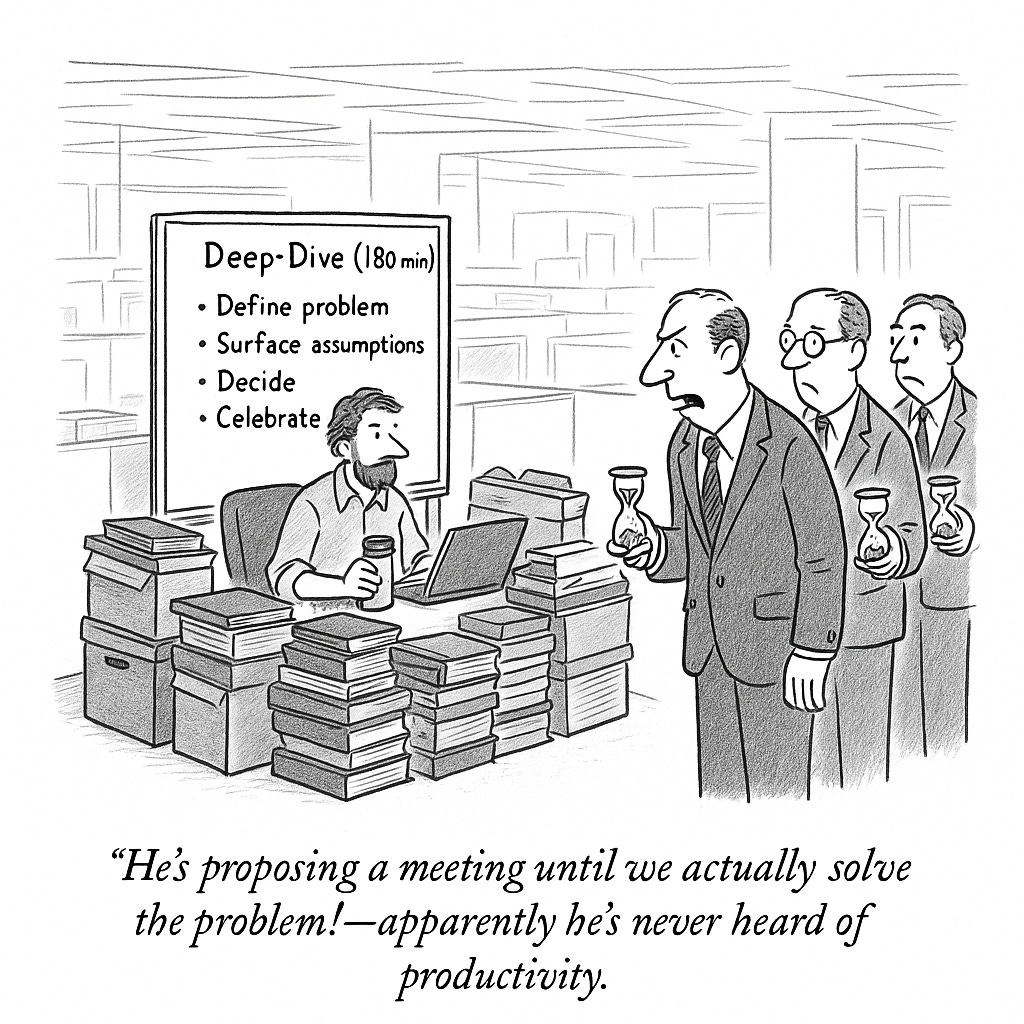

This cult of short meetings emerged a number of years back, spawning a pattern of problems that probably could be resolved in a couple of hours taking months to reach an (often) unsatisfying conclusion. It probably seemed attractive because the 30 minute constraint should bring the benefit of focus. This works well for things that can be started and finished within that time - say a quick status report, or a basic standup. But when there’s a non simple problem to be solved the “shorter meeting” often makes things worse. People start, they don’t finish and then instead of canceling other things and working through it they setup the next meeting when it fits in everyone’s schedule. If it’s a problem requiring two or more teams then the schedules get complicated and the next meeting might be a week or two out. Then the pattern repeats a fortnight later, and so on. After a couple of months someone voices their dissatisfaction and that’s put on the agenda for the next meeting. Before you know it everyone’s pissed and thinks the other team is hard to work with. Very limited, or no progress is being made.

The opposite

The answer is usually pretty simple - do the opposite. When you encounter a problem that is (a) important, and (b) can’t be solved with the 30 minute (or 60 minute) constraint then block an unreasonably long block of time to solve it. Just think and decide on;

Who needs to be in the group because they have critical information or is part of the decision. Be inclusive - but just representative. That means not everyone in every team involved needs to attend2. If they think they do, it’s worth remembering that America is a representative democracy and not a direct democracy for a reason. OK - maybe bad example at times. But hopefully you still buy the premise.

Schedule a large block of time. If you think you need an hour, schedule two instead. A few hours? → schedule a day. 8 hours → schedule a 3 day offsite. If you don’t need it all then everyone’s happy to have time given back or go out for drinks. But if the problem is worth solving then intentionally grant it the gift of focus.

Write out and negotiate an agenda as to how you’ll use the time in advance. This should be true for every meeting, and the best (arguably the only correct) agenda is negotiated. Sometimes “in advance” isn’t worth it and it’s better to just get together sooner and use the first hour or two to do that discussion. An agenda should capture what everyone views as success for that period of time. Other topics beyond success definition falls into the “best practice” to “nice to have” realm. If you don’t agree what success looks like then stop and figure it out.

Meet and don’t rush. It’s amazing how not rushing will let you bring up all the different perspectives, what would have to be true about each for it to be awesome (or just acceptable), and how everyone views the problem differently. This building of vision can get folks out of the “that won’t work” and into the “what would have to be true for that to do be possible” mode.

Write down what you agreed (and why) to. As well as the other things you discussed to remind your future selves how broad you all went.

Go have a nice dinner (or lunch if you nailed it early) to cement the positive experience and remember to not stick with the 30 minute meetings next time.

Suggesting this brave new world in practice

Next, I’m going to share a simple script that seems to work well.

I’ve been amazed at how often this works. I’ll be sitting in a 1-1 discussion with someone on my team (or a peer) and they’ll be complaining about how the other team doesn’t understand, some team member is making things take forever, and/or person (or team) X is doing something that’s just crazy. I find more often than not a combination of the three questions create a whole new plan;

What did person X say when you either (a) asked what3 made them felt that way? or (b) told them that ______ was causing you concern? Because humans in part evolved to get along it’s surprising how often the receiver of these questions will realize they hadn’t yet had a direct discussion.

What would have to be true for (insert situation/scenario) for that team to get on board? What in their world of stuff to be done makes it hard for them to agree? This can get people to think about the problem, and the problem they’re having with the other group in a more removed way. An external view is almost better for creating more possible options vs. staying stuck.

Instead of just having these short meetings/emails/slacks what if you got together in person for a day or two to just really figure this out? In today’s world common objections are likely to be about “not having time” or “not having budget for a flight.” At which point it’s time to be curious and see if a lighter version of the question (say meet for 2 hours vs. a day), or a different take on value (cost of meeting vs. cost of not solving) will unstick things.

There are days I’d argue that 50% of management is asking these questions, 30% is setting great goals (including things that are personally important to your staff), and 20% is just showing up and being curious and not-jerky.

Today’s lesson is about the bolded point above. I’ve often been surprised how quickly people embrace this idea. I’ve never been disappointed “over scheduling” of time and just getting together has been for situations that hae persisted more than 2 meetings (or 5 emails). This is one of the best lessons I took away from working at Facebook where people would commonly suggest an “offsite” when things slowed down4. At first it seemed like a poorly veiled excuse to fly to a different city, meet during the day and go out somewhere pricey for dinner. But I realized quickly that even without an agenda of any kind how productive these open ended LONG meetings could be. Dinner was also nice. ;-)

Add an agenda and a little bit of structured facilitation and amazing things happen. It shouldn’t be surprising - once you recognize that multi-tasking is the enemy of most throughout then taking the “start something, finish it, period.” ethos into the meeting realm should solve the never ending “short” meeting problem.

Some hacks for your mini offsite

Use some time in the beginning to ensure people know each other. This seems touchy feeling but even if it’s name, project/team area, most fun vacation in the last two years it’s amazing how people realizing other folk are people helps.

Negotiate the agenda before you jump right in and figure out a day later you’re off track. Negotiate here means you take the effort is an effort to create agreement between two or more parties, with all sides having the right to veto. This ability to say no is important and keeps you learning what’s truly important to everyone before you go too far.

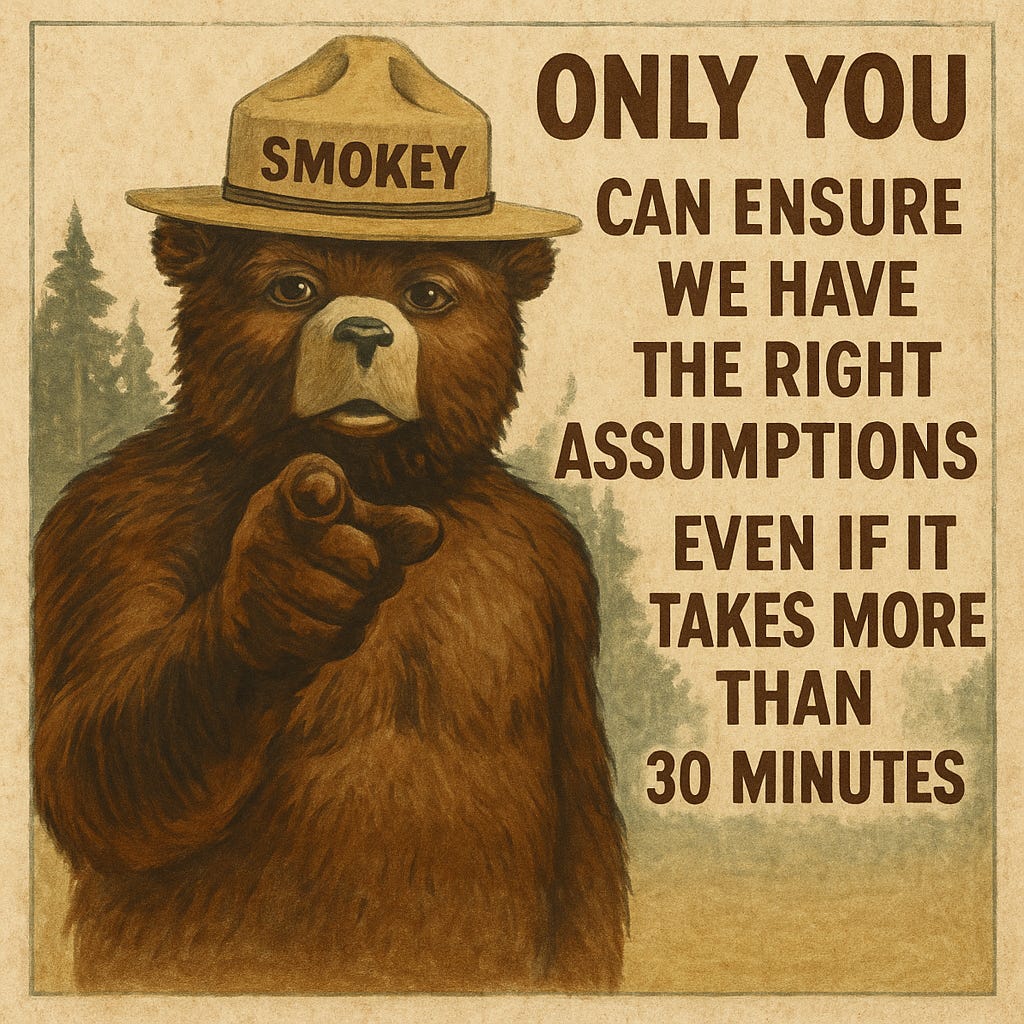

Whatever solution you’re trying to solve for, take some time for folks to surface all the underlying assumptions as to what makes the solution work or the problem hard - even if they seem obvious. Write them out on a whiteboard or post-its or the online equivalent.

When you seem stuck, try the following5

Ask the group to write out all the options even if they seem really wrong to some or all in the room. Then go systematically through each one and ask everyone to contribute “what would have to be true for me to think this idea will work?”

If you get down to an either-or choice create more options. One way to do that is to apply the vanishing options test - “if X was no longer an option, what would we do?”

If the project feels like it would take too long with existing estimate ask “what thing if we change in the expectations/requirements would cut the time required to solve something in half?” BTW - THIS IS WHY YOU WANT TO MEET WITH ALL THE DIFFERENT DISCIPLINES AT ONCE INCLUDING ENGINEERING. Oh, did I not mention that before?

If you’re really, really stuck consider writing out tenets. It’s often a good way to step back and figure out where you’re stuck. Being stuck is often a sign you have differing assumptions as to how to operate, or what’s important. I wrote up something on tenents you can read - it also links several other nice/better explanations of the concept.

If you’re stuck and you “write out tenets” easily then you’ve almost certainly done it wrong. The tenets should focus on areas of tension intentionally because they’re there to encode how to make decisions without constantly reconvening. If it’s too easy then that’s usually what was missed. Ask “why is this decsion/problem?” hard for us and that’s where you need a tenet to sort through it all.

Before you head out

Make sure folks review the written summary of what was learned, rejected, and decided.

Conduct some form of mini-pre-mortem to reality test your plan. If we take this path and it doesn’t work out what likely caused the problem?

Spend a few minutes celebrating that you worked on something for more than a short while and now truly understand everyone’s problems and views. If you don’t work for the world’s most frugal company grab dinner or something nice like that.

Say what you want about the British Empire, but they really punch above their weight in pithy phrases.

Since you’re only meeting for one fixed block vs. every week having everyone attend from all teams isn’t as bad as it is for the 30 minute meeting where most people are checking their Slack messages most of the time. But there are still costs, especially if you’re traveling. having everyone together all the time has other negative effects - a big one being that it’s no longer considered important to have great summaries of the meeting for those not there. That means no one contemporaneously agrees to the meeting summary at the end of the meeting - which opens a gap for differing assumptions to sneak in.

Just because you’ll read the following advice lots of places doesn’t make it bad. It’s generally useful if you start questions with “what?” or “how?” vs. “why?” You don’t generally want to get people’s defensiveness up and “why?” almost always does that. There are excpections to the rule - but give it a try if you don’t believe. “when” and “who” are useful - but usually best left to when you get the curiosity train moving constructively. If folks are curious about this drop a comment and I’m happy to explore this idea more.

This set of tools is pretty darn valuable in a much wider set of situations. ‘nuff said.