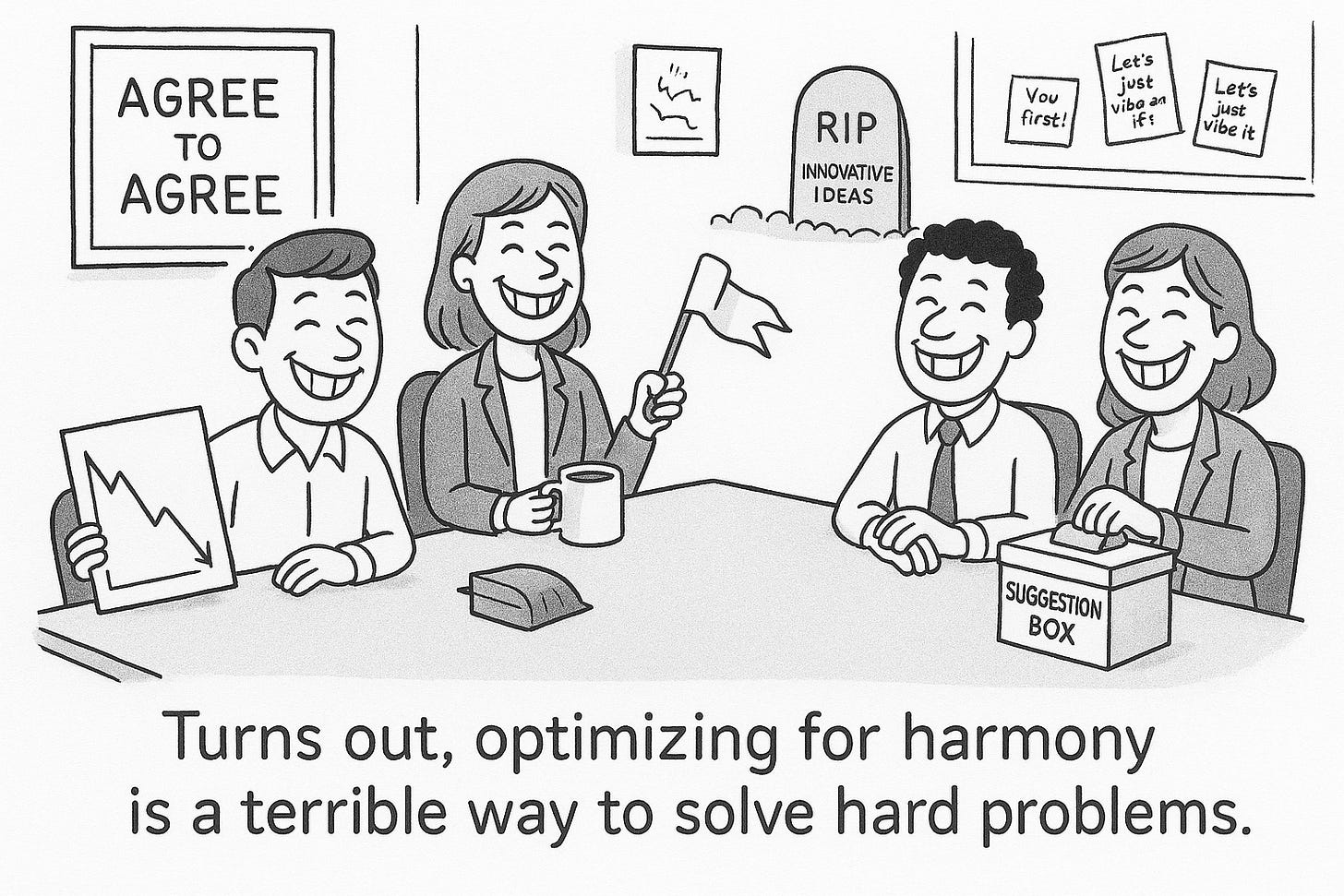

Compromise is overrated

How being too nice and avoiding conflict makes a mess of things.

Some voices got treble - some voices got bass. We got the kind of voices that are in your face. - The Beastie Boys - The New Style

I want you to be nice, until it’s time not to be nice. - Dalton (Roadhouse)

TLDR;

Being nice is pleasant, but being nice != getting stuff done. Ironically, too much being nice (in the wrong ways) makes people and teams miserable.

When teams are in conflict they are often seeing different realities. Dealing directly with these varied vantage points is the best path forward.

Stay curiously engaged with the disagreement until you’ve surfaced everyone’s underlying assumptions. Doing so increases the chance you’ll find a great solution. As a bonus, people are more likely to be happy with a decision in which they were deeply heard out on. Even if something they’d disagreed with is ultimately done.

Avoiding compromise results in better decisions with higher leverage. Compromise paths rarely are optimal for your global (read important) needs. More often they try to give everyone a little bit towards some local goal - which rarely adds up to something important to the overall enterprise.

If you really mine the disagreement down to the underlying assumptions level it’s common to find great solutions based on ideas no one had at the start of the conflict.

When you’re stuck use two simple tools

Ask everyone - “what would have to be true for each idea to be the best choice?

Still stuck? Get an external view sooner rather than later. AKA the dreaded “escalation” in corp-speak.

You’re welcome. ;-)

The downsides of premature agreement

I’ll eventually make a half hearted attempt to write a framework of some sort out on the topic of this article. Serious people seem to love frameworks. But really, my main goal here is to

encourage you to say no when you aren’t sure you agree with a plan,

encourage everyone around you to do the same,

do the hard work of constructively unearthing the assumptions underlying disagreement.

Finally, without compromise, look for what would have to be true to resolve the conflicts you’ve identified.

Even more than frameworks, statistics prove I feel everyone seems to love a story from the billionaire who’s slightly less controversial than Elon (residents of Venice excepted of course). So let’s go with that…

Jeff Bezos famously worried about social cohesion at the expense of truth. One of my favorite talking points from my Amazon years was how much the culture expected the speaking of truth to power. To disagree and not say anything was not cool, and constructive disagreement was celebrated1. That’s a culture with a higher interest in making the best possible decision than any of these other possible “goals”

Finishing a discussion quickly

being right

feeling smart

getting along with others

being see as “nice” or “flexible” by compromising

Of course there are more and less jerky ways of accomplishing this. But at it’s core it struck me from the beginning that this was a very “engineering culture” way of approaching reality. You could also argue it’s the scientific method way as well.1

Dr. Eliyahu Goldratt shares a wonderful illustration of why compromise is unhelpful. Coming from a physics based background, he argues that when people disagree about something, their views of reality differ based on assumptions they are making. Only by examining those assumptions can one untangle how they can view the same actual state of reality and believe different things. In physics the idea of compromising, splitting the difference etc. is laughable - even to the non scientist2.

‘For example," Johnny tries to clarify his point, "suppose that they try to measure the height of a building. Using one method they find that the height is ten yards, and using another the answer comes out to be twenty yards. A conflict. Do you think that they will try to compromise? That they will say that the height of that building is fifteen yards?

In the accurate sciences, what do they do when they face a conflict? Their reaction is very different than ours. We try to find an acceptable compromise. This thought never crosses their minds. Their starting point will never allow it; they don't accept that conflicts exist in reality. "No matter how well the two methods are accepted, a scientist's instinctive conclusion will be that there is a faulty assumption underlying one of the methods used to measure the height of the building. All their energy will be focused on finding that faulty assumption.’

and correcting it.’ (Chapter 11 - Critical Chain - Eliyahu Goldratt)

Everyone laughs at the idea that compromising on the height of a building is a good plan. But I’ve still seen tons of folks splitting the difference in order to get along with another team or person’s view of the world. If you’re haggling with a vendor on the price of a t-shirt then you’ll survive if you ignore the excellent advice in never split the difference. But if you’re a company that’s encouraging people to be “nice” without training on principal based negotiation/reasoning skills then those series of compromises are almost guaranteed to degrade the outputs you care about. Ironically they’ll also leave everyone less satisfied then they would be in a culture of constructive, even aggressively constructive disagreement3.

Before I recognized this problem I’d already lived an endless series of examples. Two teams are in conflict - say about whether the auction function in an adtech system should include some weighting parameter as opposed to filtering out some ads upstream, or whether a price prediction should be used unchanged from team A - or modified with some local information by team B4. They argued and argued5 but didn’t make progress. Or worse, they announced they broke the logjam by some compromise. You can usually tell this happened because they say things are resolved, but look pretty miserable when the topic comes up6.

In each of the cases I’ve seen a better choice would be to (a) agree they are stuck, (b) get some help on resolving the conflict, and (c) make their underlying disagreement more visible and then work together on a framework for how to decide on how to make a decision.

Oh … I owe you a billionaire story don’t I? I’ve got a great movie discussion one about Prometheus, but … I’ll hold that for now and share one on topic.

I was lucky enough to be in the room on an occasion when Jeff B entertained a meeting with reflections on the risks of social cohesion. A pretty notable blunder had occurred recently, and he was reflecting about his own contribution. It’s the sort of thing that felt off the cuff but I suspect may have been repeated in meetings throughout the period to organically cascade a point.7 He was chastising himself for giving in to social cohesion when he went along with a plan he suspected had a downside. It was especially interesting to me because he identified a personal “tell” that he knew he used when he was suspicious about agreeing with something but was tempted to play nice.8

Jeff also told a parable he’d recently come across where a family ends up at a restaurant that literally no one in the family wants to be at because they all assumed something about the others and didn’t want to contradict anyone. I wish I could recall the exact structure of the story as it was a great example - both funny but also something we could all relate to. Sorry! Definitely my bad. This is why one should journal consistently to benefit your future memoir.

In a previous post I was joking not-joking that people thing of Amazonians as jerks7. This is not in my view inevitable if you get people to disagree when they should and avoid compromise. Better to deal with that though than have everyone skip happily holding hands towards a giant sinkhole that one of the “nice” people knows is right there. This probably doesn’t mean everyone has to be great at disagreeing - but you need some critical mass, and probably a practice of actively seeking out the disagreement.

As the parable suggests, it’s best is someone points points out the emperor’s naked. OK class - just stop giggling now please…

But disagreeing all the time is exhausting..

Amazon balances the everyone disagreeing all the time rabbit hole with their Disagree and Commit leadership principle. Focus often falls on the “disagree” side when this principle is discussed. People often also talk about Amazon as a purely top-down culture where everyone “commits.” But when this principle works it’s because of the balance.

Employees are expected to have backbone and share when they don’t agree with something. Once everyone has been heard and a decision taking all the views into account then there are moments where it’s more productive to do something than to keep arguing. That’s the “commit” part. It is very useful, especially if teams couple it with a “tripwire” (not a common Amazon term) identifying under what circumstances they’ll revisit a decision.

The principle in practice can be seen as having three parts in my view

Expecting disagreement to make better decisions even when it’s uncomfortable

Expecting people to run with decisions that have been made

Operationally yet sets tripwires to pre-identify when to revisit choices.

I don’t have the science to back up that these are all necessary and sufficient conditions for it to work, but it passes my biased experiential test for correctness.

Different cultures get jammed up in different spots when dealing with how much to disagree and how to resolve conflict. A friend ones shared a story from a team-building event at an archery range that balances a few large tech companies. Maybe it’s apocryphal but I found it pretty funny nonetheless.

At the start of the event the range staff gave a standard safety briefing. All seemed to go fine. Afterward one of the instructors asked her where the team was from - as they were so different from some other recently hosted events. They described the experiences roughly as

Amazon: They sat through the briefing, asked some basic questions and accepted the rules as useful to prevent being injured. Then got on with things.

Microsoft: OK, I’ll admit I totally forgot what they said about those teams’ quirks were. In my defense, it wasn’t as funny as Google, and Microsoft hadn’t yet hit their second run at taking over the world.

Google: They could barely get to the actual archery because the engineers questioned and then attempted to change/improve every process step. Questioning all the way down to the basic assumptions that are typical for all shooting sports. Largely one would presume due to the physics of not being in front of projectiles at any time.

I’m sure this is unfair of me8 - though Googlers have laughed at this story in the past. But it seems like a simple example as why you do need a culture that can both argue and decide. I’m just writing all this because “compromise” as a decision framework seems more prevalent than argue all the way down culture from what I’ve observed. Also - when folks fight too much it’s usually obvious. Compromise is insidious in that teams can appear to be super highly functioning but not have the high leverage results you expect due to not making principled decisions based on global business goals.

Disagreeing constructively

Hopefully it goes without saying that it’s definitely possible to get this benefit of constructive conflict without being a jerk in how you disagree. Some tips for how to do that are explored in my article on mind reading. In short, the best way to understand another’s problems is by asking - preferably with “what” and “how” lead questions.

The reality is that none of the above came (or comes) easily to me. I’m an introverted person most of the time, and when I’m being honest also a recovering people pleaser. It requires focus and some mental hacks to be able to use my own advice.

Learn how to say No effectively, and as part of principled decision making. This book is an especially good primer on the topic. Lots of folks tell me they don’t like the intro - so feel free to skip it.

For two-way doors (decisions that can be reversed) endless arguing may be a bad way to approach things. A great way to deal with disagreement can be to commit to going forward with idea X but agreeing jointly on tripwires that would cause you to stop and re-examine the situation. If folks things that the new design is awesome but agree that higher bounce rates after two weeks would make them question the original plan then set higher bounce rates as a tripwire.

When you’re thinking about how you don’t agree with something but are hesitant to speak up consider these mental hacks to have better discussions

Say something to get the ball rolling quickly - don’t sit and ruminate on exactly what to say. I read that this is a good tip to making conversation with someone you don’t really know and it seems to work here. The longer you wait to object the harder it gets.9

If you’re still debating whether it’s worth disagreeing - try some time travel. It’s a few months later and whatever you’re worried about has gone wrong. How much is your stress then relative to the immediate stress you’re worried about from saying something now? Sometimes this will show it’s better to have conflict now vs. a lot of drama later. Almost as often you’ll see it’s not a big deal either way. People aren’t likely to really be that upset, the decision will likely be better, and if you realize you’re wrong you at least increased everyone’s confidence.

Ask some questions to build vision in the other party about what specifically they view as risky or undesirable about the solution you don’t agree with. The more curious the questions the better this works. A similar approach is to suggest a pre-mortem before you all really commit.

If it’s not so much about failure of an idea and more about choosing the “the best one” then it can be time to trot out the “what would have to be true” experience. Ask everyone to list out all the ideas on the table and get everyone to contribute their take on “what would have to be true for idea #3 to be the best.” Then sit back and look for opportunities in everyone’s not explicit assumptions.

Focus less on the decision details but more on what would be true about a great decision. Basically construct a quick, high level decision framework to see if there’s agreement on that first. Conflict often comes from differing assumptions, but a subset of this is differing goals. Some really big disagreements are caused because depending on where you sit relative to a problem the goals may be wildly different. Talking about the goals sounds “process heavy” but can cut through a lot of baggage faster than you could read 1/2 of this article.

If teams are really stuck you can ask the parties to argue the other side’s position. It’s a really interesting approach intellectually - and my intuition is it has value. But it’s a smidge theoretical one for me - a very smart coworker effectively pitched this to me once upon a time. If you’ve used it successfully I’d really like to learn more from you.

Try the bonus idea in the conclusion section :-)

DON’T BE A JERK. I’d use stronger language but I think everyone once in a while my dad forwards this to my mom. I’m sure there are cases where being a jerk makes things better, but that feels very much like an edge case.

Conclusion

Hopefully you’ve read through this and found lots of useful suggestions. Or maybe you feel it’s all pretty obvious but someone you know would benefit from it being shared with them. Or maybe you just have a soft spot for the Beastie Boys and/or Patrick Swayze’s best role. I mean you could hate this stuff but have read all the way through anyway. In that case - Thanks Dad!

Rather than recap what you’ve already read I’ll include one thing I don’t believe I mentioned10. When you get stuck - just escalate. If you’ve been disagreeing with a team (or a person) and have tried your best it’s time to get help. Most healthy orgs would prefer you get an external view to help the team decide rather than just bang your excessively well paid heads against a wall.

A short example; when I worked in Ads at Amazon there was a constant battle royale disagreement between the team that put ads at the top of search, and the team that controlled search results. Something about the purity and value of relevance vs. the debasing view of money effing everything up. The search relevance team was always looking out for our ad-loving eternally damned souls - doing lots of research to help out and explain to us find the right answer. But, as often happens in such cases we could not sort through this disagreement. Both teams excelled at not-compromising.

Ultimately, the situation needed Jeff B to truly help. From his external view came a few well placed questions about the max damage of an ill chosen ad to the search team. Given the answer he quickly calculated how often the ads would have to truly suck to be long term negative. That presented a working framework that avoided compromise and got teams unstuck. We left with a new clarity and the teams went on to operate to tremendous gains. If you’re wondering how Amazon maintains their flywheel of low customer pricing this story is part of that .

Long story short - Jeff’s departing comment was how happy he was when something this important was quickly brought to someone who could help with an external view. That stuck with me, because people often think the only options of conflict are to compromise, or argue until resolution. Sometimes one just needs a little help from a friend external viewpoint.

In 9 out of 10 respects whether you call this focus on truth “engineering” or “science” is sort of like tomayto / tomahto debate, in that the point is still the point. But I refer to it as an “engineering” culture because (a) I self identify more as an engineer than a scientist, and (b) Amazon wasn’t doing this or anything with a pursuit of general/higher knowledge - it was to get shit done that helped customers as scale. But that’s not to say I don’t love scientists. I’m a big fan of vaccines and physicists for example. Also, I still miss watching Dr. Science explain important topics such as where your missing socks go. Google it!

If you’re intrigued by this quote and what it means for reasoning about conflicts and contradictions then I highly suggest checking out Goldratt’s work. It’s not 100% magical but it’s extremely useful - at times to the point that it’s indistinguishable from magic. As described in The Choice he argues that reality doesn’t have contradictions, but it does have conflicts (such as the conflict in that an airplane wing must be both strong and light). Also - if you’re only read The Goal, there’s a lot more out there.

I don’t have definitive research to prove this point. But in my experience most of the times when teams “compromise” on something both sides feel pretty unhappy with the result and the path that got them there. I bet if you think back to an example in your past you’ll find the same. Reading Start with No is another way to convince yourself on this point, and many valuable other ones too.

A friend gave me an even simpler example recently - let’s call it the “good pasta sauce” test. Previously when their spouse made a dinner they didn’t exactly love they’d just be “nice” and say they enjoyed it. But when they made something not to their spouse’s taste hear the truth, including specifically what wasn’t quite so good. The summary of the story basically was “I realized I could keep eating the same crappy meal once a week for life, or I could say it needs a bit more sugar to balance the tomatoes in the sauce.” With apologies to generations of Italian Grandmas who are now throwing things at their screen and deleting their subscriptions over that sugar part - I think we’d all be best off calling out the missing ingredient to a dish than “sparing” someone’s feelings. Better communication = better pasta = disagreement gets to better outcomes.

See my related point about how these arguments routinely take 8-12 weeks on the calendar vs. one 4 hour focused chunk of time because folks don’t want to prioritize resolution or jump to escalation. Either being likely better for team happiness and throughput.

There’s another failure mode where the teams “reach agreement” after being forced into one super long meeting due to some goofball’s weird ideas, but then realized they still disagree a day later and everyone wants to slam their head into a desk. This is less common - I only actually observed it once, but multiple times from the parties involved. The main suggestion I have there is to attend the meeting yourself and ensure they follow through writing all the agreements out clearly so they don’t accidentally agree just from exhaustion.

Hopefully obviously I’m referring to people who work at the company Amazon, not people who live in the Amazon, nor Wonder Woman’s peeps.

I could use help from my ex-Meta teammates in slotting in how that culture would fit in. Maybe they wouldn’t listen closely to the instructions because they were clear it wouldn’t be part of their quarterly assessments.

BTW - at least for me this is pretty good advice. I used to really stress about talking to people in what really were not high cost/risk interactions. The advice to say the first thing that comes into one’s head without overthinking seems to work. You quickly discover that 90% of people really aren’t going to judge you as long as you don’t say something truly wildly inappropriate. The result is that you quickly realize the benefit of breaking the ice and listening for a response is way better than sitting there trying to craft the perfect opening line. Before you know it you can do this in all sorts of situations, and away you go.

OK - I definitely mentioned this in the TLDR - but that was a really long time ago. ;-)

Just like the old joke lawyers tell -- "you know it's a good compromise when both parties are equally unhappy"

Ah "don't compromise for the sake of social cohesion." This part of the LP is probably the signle biggest source of the 'Amhole' stereotype. Certainly a distinctive belief of the company that harmony is often overvalued in the workplace - that it can stifle honest critique or encourage polite praise for flawed ideas. One downside is that every meeting becomes a "battle royale".

I half-jokingly tell people that this scene (linked below) is a good depiction of a real life Amazon meeting. It's from S1 of the Star Wars TV show Andor.

https://youtu.be/iKl0F640914?si=PrBlp0rHBNE9Y73g

Side note, I suspect that Bezos would score very low on 'agreeableness' on a personality test. Not meant as a diss, but agreeableness is a trait in psychology quantified on a sliding scale similar to introversion/extroversion. It's kind of a poor name since saying one is "disagreeable" has a negative connotation. Would also not surprise me if folks in company leadership also generally score low on agreeableness. Check out the "Big 5" personality traits.